The use of cash fell substantially in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic with the acceleration in online shopping and contactless payments – but cash usage has bounced back as lockdown has eased. Long-term prospects for retail payments remain uncertain.

It is still too early to tell whether Covid-19 and the public health interventions implemented in response will have permanent effects on retail payments in the UK.

Initially, the hoarding of cash was overshadowed by an acceleration in e-commerce and contactless payments, an increase in the use of mobile payment apps and – some speculated – the possibility of cryptocurrencies becoming mainstream. This happened while bank branches closed (some for good), as many as 9,000 ATMs (15% of the total) remained idle and the media falsely reported a high risk of transmission through banknotes.

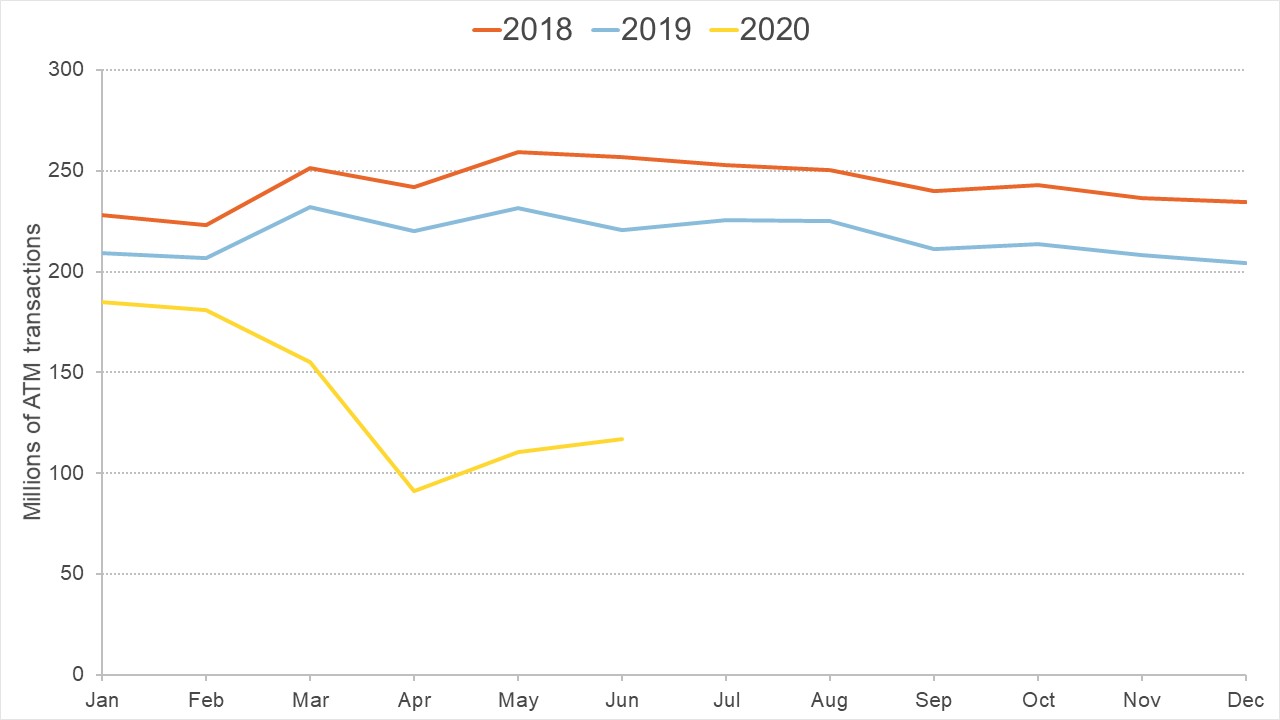

But despite these apocalyptic messages and the initial negative shock leading to a severe contraction in the use of cash, transactions using banknotes and coins began to recover even before lockdown eased, as Figure 1 suggests, while cash usage increased by two-thirds after lockdown measures eased.

Figure 1. UK transaction volume in the LINK ATM network, 2018-2020

Note: These figures include balance enquiries and rejected transactions made through the LINK network, but do not include transactions made by customers at their own banks’ or building societies’ ATMs.

Source: LINK, 2020.

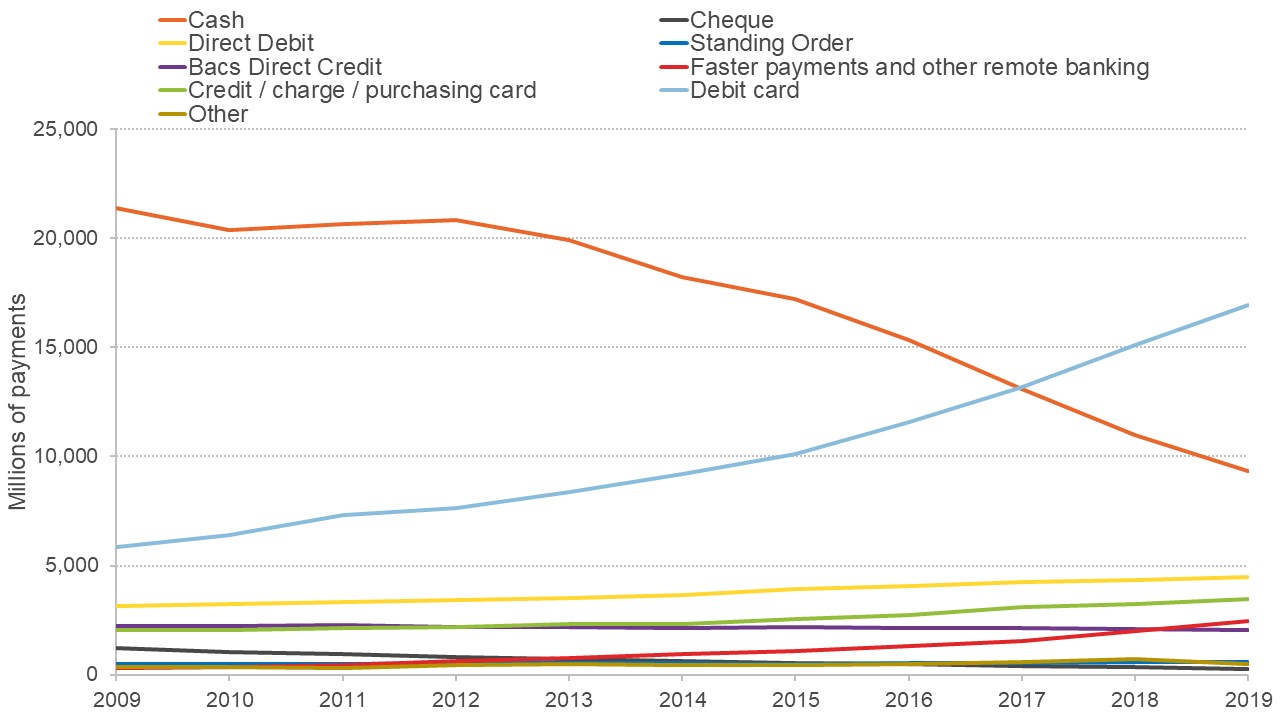

Before Covid-19 struck, digital retail transactions in the UK were on the rise, as Figure 2 indicates. Ten years ago, cash was used in six out of 10 payments. As late as 2016, cash accounted for 40% of all payments and 44% of all payments made by consumers in the UK.

The adoption of contactless payments in public transport networks, increasing e-commerce, widespread use of plastic cards and digital payment applications – for example, Apple Pay, Samsung Pay, PayPal and iZettle – as well as the increase in ‘tap and go’ payment limits, boosted digital payments.

Industry group UK Finance reported that the proportion of cash transactions was 28% in 2018 with an expectation of it dropping to 9% by 2028 (UK Finance, 2019). The long-term downward trend in the use of banknotes and personal cheques indicates that neither will dominate on-the-spot transactions ever again.

Figure 2. UK payment volumes, 2009-2019 (millions)

Source: UK Finance, 2020.

But it is too early to tell whether the trend of declining use of cash and personal cheques accelerated in the context of Covid-19. The acceleration implies a long-term structural change within retail payments rather than on other parts of the transaction economy (namely online versus bricks-and-mortar, financial inclusion, bank facilities – ATMs, branches, self-service, etc.).

Recent attempts to rush the UK economy to rely solely on contactless and digital payments have highlighted deep-rooted inequalities and the need for access to cash by some communities (including vulnerable consumers). Anecdotal and mass media reports suggested that joblessness associated with the Covid-19 pandemic might have increased the demand for cash by people in the lowest income strata and those living in rural areas.

These trends, in turn, point to the following major issues:

- A need for a better understanding of why some consumer groups remain in a cash economy (Ceeney et al, 2019; Alabi, 2020).

- The importance of a resilient back-up within the retail payments infrastructure.

- Finding ways to achieve an orderly resizing of the UK cash distribution cycle (Bank of England, 2020).

- The consequences and drawbacks of the abolition of cash (Seitz and Krueger, 2017).

Related question: How is coronavirus affecting the banking sector?

What does the evidence from economic research tell us?

Short-term impact: a shock to the system

- An initial hoarding of cash (Ashworth and Goodhart, 2020) and an unprecedented surge in the demand for gold as a store of value (Lepecq, 2020a).

- The possibility of viral transmission through banknotes and coins. But laboratory studies (including one by the European Central Bank) suggest a higher chance of transmission through stainless steel and plastic surfaces than cash (Bank of International Settlements, 2020).

- In the UK, over 80% of banknotes are distributed through ATMs. Precautionary steps had to be taken by central banks and financial institutions to supplement their cash inventories as retail bank branches closed while some ATMs became idle (for example, at airports and casinos) and others experienced intensified use (for example, in supermarkets).

- But the cash distribution infrastructure (for example, the number of ATMs, security vans, retail bank branches, clearing centres, etc.) was designed to fit a bygone era and is currently thought to be ‘oversized’ as it faces declining demand. It is deemed not fit for purpose in the UK (Bank of England, 2020).

- Innovations in retail banking systems are incremental (Bátiz-Lazo and Wood, 2002; Bátiz-Lazo, 2018). Not surprisingly, during the past few months, no single digital payment solution has been tremendously disruptive or become a clear ‘winner’. Indeed, it is to be expected that some solutions will be adopted, some discarded, and some changes will only be transitory.

- The fortuitous and incidental innovative nature of cryptocurrencies is evident as they remain invisible within the high street, while most of their volume emerges from speculative market trading (Hu et al, 2019).

- The recent demise of Wirecard, the German fintech champion, raises questions about whether an accelerated shift to digital payments exacerbates participants’ risks in terms of both compliance and costs (Krahnen and Langenbucher, 2020).

- Through their dominance of e-commerce, social media, messaging, taxi-hailing and other platform services, Asian apps – such as QQ and WeChat in China or Go-Jek and Grab in Indonesia – provide a simple solution to connect their mass market users with their respective mobile wallet products – Ali Pay, WeChatPay, GoPay, GrabPay, respectively (Aveni and Roest, 2017; Yunus and Pamungkas, 2018). The Asian cashless experiences have yet to be replicated in Europe and North America as indigenous platforms – Uber, Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Skype, etc. – rely on plastic cards for payment.

- Global supply chains have been disrupted causing a contraction in cross-border payments – for example, a purchase in Amazon.co.uk being billed through Ireland or Luxemburg.

Long-term impact: potential structural changes

- There is and will be greater competition among individual providers of credit and debit cards, or between payment cards and digital solutions, than between any of these and cash (for example, Brown et al, 2020).

- As a single, independent payment solution, the volume of transactions with banknotes will continue to outpace any other single provider for settling on-the-spot transactions and small value payments.

- The Visa-Mastercard duopoly position as chief clearing platforms for domestic and cross-border retail payments will remain unassailable (pending the success of national initiatives such as those in China, India, Russia and the European Payments Initiative).

- Consumer surveys sponsored by central banks consistently suggest that over 70% of respondents and particularly those currently using banknotes in retail transactions have no plans to go cashless (for example, Cleland, 2017; Chen et al, 2020), prompting questions about whether the needs of vulnerable sectors of the population with a strong preference for cash can be accommodated.

- The relevance of redundancy and increasing organisational resilience has become apparent since the exposure of global supply chains to the economic disruptions of Covid-19. Vulnerabilities and failures of digital payments have been evidenced on many occasions, for example, in the Great US Northeast (and Ontario) Blackout of 2003, the flooding and destruction of the electric infrastructure of Lower Manhattan after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the Visa outage of May 2018, and the hacking of Japan’s 7-Eleven smartphone payments service.

- It has been argued, while not empirically supported, that cash hoarding by financial institutions prevents a deeply negative interest rate policy as well as reducing corruption and tax avoidance in the ‘shadow economy’ (Rogoff, 2016). Steps aimed at preventing illegal transactions and diminishing the size of the informal economy (while aiming to improve countries’ fiscal positions) could thus lead governments to support and encourage cashless payments in a way that they have not done before (for an opposite view, see McAndrews, 2020).

- Applications of technology can help to increase financial inclusion (Demirgüç-Kunt et al, 2018; World Economic Forum, 2011). The role of state actors is critical in the genesis and dissemination of these technologies (Batiz-Lazo et al, 2020). But increasing evidence of financial inclusion leading to over-indebtedness among people living in poverty (Anderloni and Vandone, 2008) and the apparent superiority of direct cash transfers to the economically vulnerable raise questions about financial inclusion as a goal and its effectiveness as a policy tool (Duvandack and Mader, 2019).

How reliable is the evidence?

Although there were calls to replace notes and coins with paper cheques as early as in 19th century France (Baubeau, 2014 and 2016) and Edward Bellamy proposed a credit card in his 1888 utopian novel (Bellamy, 1888), the modern idea of a cashless economy emerged in the United States during the 1950s, as banks adopted computers and faced the rising cost of processing paper cheques (Batiz-Lazo et al, 2014).

Despite this long history, there are no systematic studies of changes in means of payment during pandemics or health crises. Nonetheless, the evidence cited above emerged predominantly from peer-reviewed journals and reports from national and supra-national institutions with responsibilities for oversight of financial markets and institutions accumulated over the past 30 years and during the early months of the current pandemic.

As countries begin to exit lockdown and with the threat of a second wave of infections, it will take a while until we can confidently assess the effects of the global pandemic on the public’s long-term use of cash.

UK Finance provides readily market information but it is only available to members. LINK, the single operator of ATMs, provides regular, freely accessible information on cash distribution volumes. Central banks have scheduled surveys of consumer demand and payment preferences for the autumn of 2020 and mid-2021.

What else do we need to know?

Short-term: ascertaining the force of the shock to the system

Previous economic crises, including that of 2008/09, were associated with a strong ‘unexplained’ increase in the demand for cash, leading to suggestions that such a shift could be related to increased uncertainty (Jobst and Stix, 2017). Rising unemployment has the potential for individuals to lose access to credit facilities and even bank accounts. These individuals might turn to cash as the ultimate budget management tool.

What will be the impact of Covid-19 on the profitability of Independent ATM Deployers (IAD) and, in turn, the location of free-to-use ATMs? In this regard, a consultation was underway before lockdown (see Payment Systems Regulator, 2019). It is unclear how recent events will modify the recommendations of that consultation.

Policy concerns about the reduction in the number of bank branches and ATMs in the UK pre-dated lockdown (for example, Bank of England, 2020; Payment System Regulator, 2019). There is a potential to increase the number of ‘underbanked’ users and unbanked communities if Covid-19 further reduces transaction volume at physical bank branches and ATMs by accelerating a move towards cashless payments, e-commerce and online banking services. It remains to be seen how non-banking intermediaries, participants in ‘shadow banking’, and fintech start-ups respond to the challenge (see Lepecq, 2020b).

At a time of major economic contraction, investors’ appetite to continue funding fintech start-ups remains to be seen.

Related question: How is coronavirus affecting the creation of new firms and new jobs?

Long-term impact: the nature of structural change

Consumers ultimately have no clarity as to the cost of using alternative means of payment. This involves both pecuniary costs (for example, commissions) and non-pecuniary costs (for example, traceability of transactions, loss of anonymity and fraud). Research is mostly mute on these topics.

Innovations in digital retail payments have been mostly incremental while bank-based systems (such as contactless mobile payments, digital wallets or card-based e-commerce) will continue to dominate the trend towards digital transactions. In other words, it is unlikely that a shock like Covid-19 and lockdown will by itself originate a payment innovation.

It is unclear whether there will be a political appetite for an accelerated move towards a cashless economy considering some of the socio-economic groups it would potentially put at a disadvantage in terms of accessibility, financial inclusion and financial literacy. All of these issues cross lines of age and gender, income and wealth levels, race and ethnicity, and the urban/regional divide (in particular the case of London and the south of England versus other parts of the UK).

The regulatory landscape

Other than General Data Protection Regulation, there is no framework for determining access to and exploitation of digital transactions. National and local policy-makers have relied on aggregate card usage data as a high-frequency proxy for economic performance to understand the extreme shifts in consumer expenditures caused by the pandemic and lockdown, and to design targeted policies to support the most affected sectors.

Systematic studies based on credit and debit card transactions are beginning to emerge, such as one for France by Bouine et al (2020) and one for Mexico by Campos-Vázquez and Esquivel (2020). But questions remain about privacy, particularly in countries without a robust regulatory framework protecting users’ personal information.

Related question: Do we make informed decisions when sharing our personal data?

As a large and complex infrastructure, it is unclear the extent to which the payments system complies with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (other than those relating to financial inclusion and gender). It should also be subject to a climate-resilience stress test.

Where can I find out more?

NEP-PAY: NEP Report on Payments Systems and Financial Technology is a free weekly list of the most recent contributions to the economics and business research on payments systems and financial technology.

Counting On Currency’s Cash Per Diem is the blog of Daniel Littman (formerly of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland) where he comments on news and stories on currency and payments from around the world.

Consultant and industry practitioner David Birch‘s 15Mb blog offers on-the-edge takes on digital financial services.

Graham Mott’s LinkedIn updates provide his insights as strategy lead for LINK on the use of cash and the ATM market in the UK.

UK Finance’s Payments Reports and Publications offer data, webinars and research on the UK payments ecosystem sourced by the trade group representing the banking and payments sector.

Webinars:

Who are UK experts on this question?

- Ross Anderson, Cambridge University

- Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo, Northumbria University (Newcastle)

- Santiago Carbó-Valverde, Prifysgol Bangor University

- Markos Zachariadis, Manchester University